On the fourth Monday in May we observe Memorial Day, a

commemoration that originated in the years immediately following the Civil War.

It was known in early years as Decoration Day because it provided an

opportunity to visit and adorn the graves of soldiers who made the ultimate

sacrifice in service to their country. Gen. John A. Logan, leader of the Union

veterans group Grand Army of the Republic, called for the first national day of

recognition to be held on May 30th, 1868. “We should guard their

graves with sacred vigilance,” Logan instructed, “Let pleasant paths invite the

coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no neglect, no

ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we

have forgotten as a people the cost of a free and undivided republic.”

What began as a day devoted to the fallen servicemen

of the Union and Confederate Armies became something more in the wake of World

War I. America lost more than 100,000 military personnel during our two-year

involvement, and by 1920 those fallen men and women were also being honored in

Memorial Day ceremonies. The Great War left another mark on Memorial Day as

well. The red poppy – warn on a lapel or handed out on the corner – is a symbol

that can be traced back to the atrocities witnessed on the battlefields of WWI.

Many will be familiar with a 1915 poem penned by

Canadian physician John McCrea, “In Flander’s Field,” which opens with the

lines “In Flanders fields the poppies blow, Between the crosses, row on row.”

Less well known is the poem written in 1918 by a YMCA staffer named Moina

Michael, titled “We Shall Keep the Faith,” in which the author promises to wear

a poppy in honor of the dead. Michael is credited with creating the

now-ubiquitous tradition of wearing a red poppy on Memorial Day. By 1922 the

Veterans of Foreign Wars had adopted the sale of poppies a major fundraiser for

disabled service men and women.

The American flag plays an important role in most

Memorial Day commemorations. The traditional flag raising practice on the last

Monday in May is unique. After being briskly hoisted to the top, the flag is

solemnly returned to half-staff in memory of all those who have perished in

service. At noon the flag is returned to the top of its staff, symbolizing that

“their memory is raised by the living, who resolve not to let their sacrifice

be in vain, but to rise up in their stead and continue the fight for liberty

and justice for all,” according to the VFW Auxiliary.

Please take a moment on Monday to remember the true meaning

of Memorial Day, participate in a local program, or simply observe the National

Moment of Remembrance at 3:00pm. If you’d like to learn more about how World

War I impacted Latah County, please visit our exhibit in the McConnell Mansion.

Museum hours and additional information can be found at www.latahcountyhistoricalsociety.org.

LCHS Photo 15-02-006. A parade through Troy to celebrate Armistice Day, November 1918. The procession of local enlisted men was led by members of the Grand Army of the Republic and veterans of the Civil War.

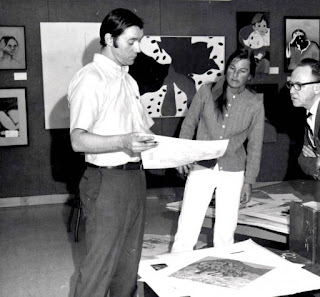

LCHS Photo Loomis.D.01. Dudley Loomis as a

high school student in Moscow, before enrolling at Idaho State University.

Loomis joined the Army in 1917 at the onset of American involvement in WWI. He

was killed in a training accident and was the first local casualty of the war.

The American Legion Post #6 is named in his honor.

LCHS Photo 01-08-056. Local residents

participate in a Memorial Day ceremony at Ghormley Park in the 1960s, which

included decorating the Ghormley memorial stone. Adorning monuments with

flowers and flags is a tradition that goes back to the earliest commemorations

of Decoration Day.